Last Fall, I attended an amazing workshop featuring Bob Bailey at Say Yes! in Canada. I think the highlight for nearly everyone was the presentation by Bob on the second day where he coached one of the attendees through the process of adding a cue. The steps are subtly different from what most of us in the positive reinforcement community have been doing for decades, but the intellectual basis is completely different, so it pretty much blew the mind of everyone in the room. Here’s a video I found online of Bob coaching a different person through this process. Go watch it and I’ll meet you back to get into the details of what you’re seeing.

[

Now that you’ve watched the video, I’m going to quickly digress to describe the process most of us have been using for years, for those who are not familiar or for a refresher for those who have used this method before, the “usual” method R+ trainers have used is to get the behavior occurring in a “loop” that goes roughly like this: dog offers target behavior, trainer marks and rewards in such a way that the dog is set up to repeat the behavior. For example, if we were teaching sit, the dog would have been shaped to offer sit, the trainer would click when the dog sits and then might toss the treat behind the dog so that the dog can return and offer sit again. Once we’re at that point, the trainer would simply start to say the cue “sit” as the dog turns from eating the treat. Note: Bob completely disproves of throwing treats around like this. But let’s go with it for the sake of argument.

After the dog has done that a few times, then the trainer can sometimes not give the cue when the dog is returning from eating the treat and then not mark and reward for the off-cue responses. This is known as “extinguishing” the off-cue responses.

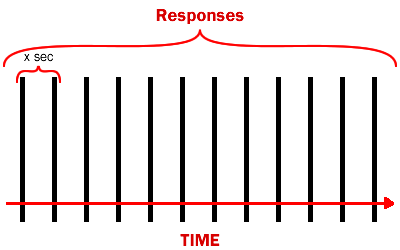

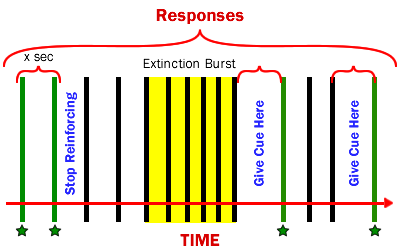

In the “new” method, we simply swap the extinguishing of off cue responses and the adding of the cue. If you’re like me, you just did a double-take and said “what? how?” So let’s break this down. When a behavior is ready to be put on cue, it will look like this:

You would ordinarily add the cue in the interval between behaviors, but instead, you will just wait until you get a gap that is just a little bit longer than your interval above. For example, if a normal cycle is “dog sits, you throw the treat, dog sits” and the time between the moment you release the dog to get the treat and the next sit is usually four seconds, you’re going to wait until you haven’t had sit (or any other offered behavior) for at least four-and-a-half seconds.

If you’re really lucky, the dog will just give you the four-and-a-half seconds, you’ll give the cue, the dog will sit, you’ll reinforce and it will all be unicorns and rainbows. What usually happens, though, is an extinction burst, where the dog offers the behavior more often than your baseline. So you may be waiting a while to get your four-and-a-half seconds.

You would ordinarily add the cue in the interval between behaviors, but instead, you will just wait until you get a gap that is just a little bit longer than your interval above. For example, if a normal cycle is “dog sits, you throw the treat, dog sits” and the time between the moment you release the dog to get the treat and the next sit is usually four seconds, you’re going to wait until you haven’t had sit (or any other offered behavior) for at least five seconds.

If you’re really lucky, the dog will just give you the five seconds, you’ll give the cue, the dog will sit, you’ll reinforce and it will all be unicorns and rainbows. What usually happens, though, is an extinction burst, where the dog offers the behavior more often than your baseline. So you may be waiting a while to get your five seconds. Finally that magic moment will arrive and, if you don’t miss it, you will give the cue and if everything lines up, the dog will give you your behavior, you’ll reinforce, rinse, repeat. Finally, you’ll see a calm, centered look in your dog’s eyes you have never seen before and you’ll see him deliberately pause and wait. Give the cue and you should see the dog calmly and with absolute certainty do the behavior. This is a breakthrough, but we’re not done. I’d give the dog a few minutes’ break on a mat or in a crate, then pull him out for a few more reps to make sure you really have what you think you have, then end for the day.

Here is a playlist showing the process of putting a behavior on cue with my young dog, Arya. I don’t claim to be an expert in this method, but hopefully it will give you some idea of what this might look like in the real world.

The next day when you come back, one of four things is likely to happen:

- Your dog will start offering the behavior over and over.

- Your dog will start offering one or more other behaviors.

- Your dog will not offer behaviors, but when you give the cue, nothing will happen, or the dog will offer a different behavior.

- Your dog will do nothing and wait for a cue.

Let’s look at each one in turn and I’ll share my thoughts on what each means and what you should do about it.

Your dog offers the behavior over and over

This is the most likely result for green dogs. To understand why, go back and look at what the rate of reinforcement does during the first session/set of sessions when you’re putting the behavior on cue. Is it just me, or does that look very like a variable schedule of reinforcement? Yes, I know that from the trainer’s perspective that we’re reinforcing every response that meets criteria, but I suspect that until the dog truly understands this process of adding the cue, the discriminative stimulus doesn’t mean that much in terms of whether we’re boosting the behavior’s resistance to extinction. My own experience with extinction is that the very best way to increase a behavior’s resistance to extinction is to stop reinforcing it until it’s nearly extinguished and then bring it back from the tiny sparks of the behavior that are left. Which is what we’re doing here.

This is what I experienced and what several other people I have talked to who have tried this who didn’t have full information on selecting behaviors to teach this process experienced. I think it’s pretty normal and expected—but when you hear that this is the fastest way to add a cue this will catch you by surprise. It’s not instant, and it’s not easy (at first). But it does eventually give you a much more solid understanding of cues and every behavior you add a cue to this way is very resistant to extinction.

Your dog offers one or more other behaviors

Most of us work on a lot of different behaviors at once. If you want to use this method, you need to have several training periods1 in a row where this is the only behavior you work on. An exception to this is if there is some other stimulus that makes it clear what behavior you’re working on such as if you put down a perch you’re expecting something to do with a perch and if you don’t you’re expecting whatever the behavior of the moment is that does not involve a perch. More on this later.

If you get this, try spending several sessions getting back to the point where your target behavior is the only behavior offered, then try again. Note that this adds reinforcement history for the offered/off cue version of the behavior, so expect the behavior will take longer to put on cue now.

The dog does not offer behaviors, but does not respond correctly to the cue

This happened to me the first time I tried to use this method, and I believe I was too successful in extinguishing the behavior. I tried just waiting it out, but I didn’t get enough correct responses quickly enough after the cue to get back on track.

I wound up going back and getting the offered behavior before trying again.

Again, if you have to do this, you’re increasing the reinforcement history for the off-cue behavior, so expect that you’ll have to wait longer before you get the pause, and then you may have to wait it out more times.

I was lucky enough to get a last-minute ticket to Think! Plan! Do! Bob Bailey and Friends! In Hot Springs, AR in May. There were demos with four dog/handler teams, and when this situation occurred, Bob coached them to repeat the cue–something most of us have been thoroughly cautioned against. To be clear, this is not “sit, sit, sit, sit, sit,” but “sit,” <2-3 second pause> “sit.”

Your dog does nothing, then responds correctly to the cue when you give it

This is what we want. You’re good to go.

What’s next? Move on

For me, the above was the easy part. I found it much harder to figure out how to integrate new cues taught this way back into Arya’s repertoire of existing cues. I think this was mostly because I didn’t really have a great system for integrating new cues into a repertoire and this showed every glaring hole in my understanding of how to do that. This process kind of reminds me of when I switched from a closed-hole flute to an open-hole flute in high school. I slipped down several chairs to begin with, but I ultimately had much better fingering.

I think the key is to handle this as carefully as you would anything else. First, test your new cue against one well-known existing cue (for example if sit is new, you might work on testing it against down). Use mostly your new cue, because that’s what you’re trying to build a reinforcement history for. If that goes well, do more of the well-known cue. Then add a second cue into the mix, for a total of three.

If at any point it’s not going well, stop and figure out what you need to change to get success. Don’t just keep banging on it like I did. But it’s perfectly ok to go bang your head against a wall somewhere.

The same goes for new environments. Don’t take your shiny new behavior to the training center around 30 dogs and expect they’ll respond correctly to the cue. They might, but why take that chance? Instead, take it to the kitchen, the hall, the bathtub, the park, your neighbor’s front lawn. Again, voice of hard experience here.

This can be fast, but it’s not magic, so you still have to use common-sense good training practices.

Why does it work?

I have not heard Bob give a theoretical explanation of this, but I was listening to a podcast where Alexandra Kurland, Sarah Owings, and Dominique Day were discussing cues. Alexandra said something to the effect that she didn’t understand for a long time why dog trainers worked so hard to remove all the incidental cues that crept in during the shaping process—the body language, the facial expression, possibly the environment. She believed that those things could just be grown into the final cues for the behaviors.

And that’s fair, if you actually know and have control over the real cue and the real cue is something that’s useful. If the cue is you’re facing left in a certain corner of your living room, that’s likely not to work well in competition, for example. Or if the real cue is you’re slightly raising your left shoulder, that may not be allowable body English, depending on the sport. More importantly, the cue you thought you were teaching might be something completely different than the shoulder raise, and so you might not give that cue when you’re asking for the behavior.

You probably thought that was a digression, so let me tie this back together. I think that the reason this works is because by waiting for the offered behavior to extinguish, you’re stripping off all of those other cues (or as many as you can) as potential discriminative stimuli. So when you offer the real cue, as long as you’re not inadvertently throwing out other cues, that stands out as the actual cue.

But still, as with us when we learn a new language, it takes time and repetition to associate the cue with the response.

Tips and tricks

- Get the behavior as quickly as you can. The longer it takes you to shape the behavior, the longer it will take to extinguish off-cue responses

- Once it’s reliably being offered, start putting it on cue ASAP. The few papers I could find talking about extinction and resurgence (which I think is what we’re playing with) only reinforce 20 responses before putting behaviors on extinction. Since I found that in more than one place, I wouldn’t be surprised if there’s research supporting that number, but I didn’t find it. What I did find is that if you can get reliable behavior with 20 reps in a row over several sessions, this seems to be enough. To be clear, that’s 20 total, not 20 per session. I also l like to see my time from offered behavior to offered behavior, including treat delivery, of 4-7 seconds. Bob is more aggressive, he says any time you get four out of the last 5 meeting criteria, go ahead and add the cue right then, whether you planned to do it this session or not.

- Plan for rate of reinforcement to fall, possibly dramatically, while you’re going through extinction. Compensate for this by giving more treats per correct response. You’ll hear him say that in the video where he’s coaching someone through adding a cue above. I’ve had ROR go as low as 1 in 50 seconds, probably due to my inexperience with this method (I was sticking with don’t repeat the cue). But it does come back up.

- After a lot of discussion on a forum that came out of the Think! Plan! Do! seminar, Bob suggested that a nose touch is the best behavior to use to teach this process—even for a dog that already has this behavior, because it is so easy to control the environment for this behavior and because the criteria are very cut and dried. He posed a thought experiment about what the process might look like if you shaped touching multiple different objects on different cues, just to teach the process. To my knowledge, no one has finished trying this and reported back.

So does it work faster?

I’m going to say my experience with the first several behaviors is no. And the reason for that is I have to be much more thoughtful and careful in teaching new behaviors. It takes several periods of working on the same behavior before I’m ready to add a cue. Each period will occur on a different day. And then I need several more periods to feel confident the cue is added. And then several more to integrate the new behavior into the repertoire.

This means that from initial shaping to having the cue starting to be added to the repertoire is going to be a week or more, during which I probably am not adding any other new behaviors. At best, I might be able to add one that has a dramatically different stimulus picture. With my previous dog, I shaped a lot of different behaviors at the same time, and since I was actually using a lot of different cues before starting to add the “real” cue, I never saw an issue switching from one to another on the fly.

I think ultimately it will be faster, because it will force me to clean up my mechanics and find faster ways to get behavior. I also already see Arya starting to develop a real understanding of what cues really are. That not only should speed up the process for her, it has already resulted in a much more thoughtful work style than Lackey has.

We’ll see. Happy training!

Special note of thanks to Margaret Simek of One Happy dog for first mentioning this technique on her podcast and for her demos at Think! Plan! Do!. She has a Cues You Can Use course covering this material based on her more-experienced perspective, which I am strongly thinking of taking.

The best thing I can do is point out when a dog learns cues this way the dog learns the process and you don’t much in the way of extinction bursts. Cueing becomes an almost instantaneous learning process. The dog gives behavior several times and is given reinforcement. the dog gives the behavior and suddenly there is no reinforcement. The dog does it a few more times, and gets slower, not faster, and then stops and looks “expectant.” You give what you want as the cue and the dog quickly responds with the behavior. In a demo, Margaret Simek wanted to cue a hop up onto a chair. She did the behavior 4 or 5 times with no cue and reinforced. It was awkward for the dog, but the dog got it. She then suddenly no longer reinforced the behavior of getting onto the chair. The dog did it once, then again, and again, then, slowly, again, and then, after getting off the chair, just stood and stared at Margaret. Margaret said HOP UP, the dog, with only slight hesitation jumped up on the chair. From that time on, the dog never made a mistake. There was none of the extinction burst, or anything like it. And, that is the way Margaret’s dog, Shine, is with cues-very fast. The dog has learned the process. For people having a particularly difficult to wrapping their head around this, I use the 10 object touch exercise. For dogs, and trainers, not taught this way before, I will say it is NOT faster. But, in virtually every case where folks have mastered the simple, but not easy, approach, their dogs get cues much, much faster. The dogs learn the game. Theory? It has to do with the salience, or relevance, of the cue. start with behavior>>reinforcement repeated. Then no cue behavior>>no reinforcement Then cue>>behavior>>>reinforcement. It is the association of cue, behavior and reinforcement the dog learns. If the cue is given every time along with the behavior, the significance or salience of the cue is lost, and won’t be gained until the delay begins when the trainer start “proofing” the dog. That means when the dog gives the behavior and you don’t say the word, then no reinforcement. So, what is that step? It is extinction. Thus, all I really do is omit that step of giving the cue while the dog is doing the behavior. The Brelands had that nailed 50 years ago, but it was rejected by trainers of the day. The Brelands actually caved on this one when teaching the public. If they didn’t they were excoriated by the other trainers and the public was advised not to listen to them. The Brelands finally abandoned the public dog training world. They were doing well with their commercial enterprise. The point in bringing this up is that training methodology can sometimes appear to be more religion than science or craft. Be prepared to try new ideas, even if you have to develop new skills.

Hi, Bob!

First of all, thanks so much for providing more feedback and context.

I agree with you that it becomes much faster to start adding the cue, as you said. This video is from February, and now, in June, Arya is quite a lot faster in initial acquisition of a cue. However, so far I find that only applies to 2/4 parts of stimulus control, animal does behavior in response to the cue and animal does not do the behavior in the absence of the cue. I have not found it helping me with the other 2 (animal does not do other behaviors in response to the cue and animal does not do the behavior in response to other cues). And I think this is where people will struggle–using the other method, you just go back to getting offered behavior and then once that’s solid again you start saying the cue just before the behavior. In this case, if you’re adding the cue after 4/5 correct responses, you don’t even have that solid a behavior to fall back on.

The behavior Margaret was having to take out of the chain was her cue discrimination, because her dog was responding to one cue with the behavior that goes to a different cue, so even a person and dog who have long experience with this can fall afoul of it. She said herself that in some instances he was just guessing–and those rule changes were announced 18 months ago. To be fair, probably 90% of people are going to turn the wrong way at some point if you tell them to take a left turn, right turn, left, left, right, left, right, right. We all very well know what left and right mean, but we don’t have perfect fluency on correctly discriminating between them under pressure. Yet we ask exactly this of our dogs. So I guess what I’m trying to say is that the path between the first attachment of the cue and being able to randomly give any cue the dog knows at any time and get a correct response isn’t really clear to me, and Margaret’s demos didn’t clarify it. Since she was demoing intervals, not the progression of cues, she simply dropped out the cue discrimination whenever Shine would fail.

There are still a lot of trainers out there who know very well you don’t have to hurt your dog to achieve great behavior, but still won’t do it because it would mean they would lose the progress that feels so hard-won. If that had been my attitude, I would never have crossed over during a time when the number of positively-reinforced dogs doing well in my sport stood at 0. But if the goal is widespread adoption of this technology (or even having significantly more professional trainers using it on their own dogs), we need to be able to demonstrate on our own dogs that it actually is faster all the way through the process and be able to support people willing to try it, but who lack the confidence to set themselves back temporarily to be in a better place to move forward.

Question: What is the longest “wait” or duration of a cued behavior do you have where reliability is at least 90% to 95%? What is that behavior? Do you have several? Now, I am NOT speaking of cueing as Margaret was, where the cues were coming, at times, like a machine gun. I mean when you give the cue to sit and the dog sits like Buddha and for many minutes waits quietly for what happens next.

It depends on which dog you’re speaking of. Lackey is on record with the AKC with being able to do one-minute sit-stays and down-stays haha, but for example the last training session I did before Think! Plan! Do! he did a down stay in a field of ground squirrels while I practiced karate for 10 minutes or so and people went by with several off-leash dogs (I was practicing karate–it is good for me also to work under distraction).

Arya can go 3-5 minutes at station under moderate distraction (outdoors in an unfenced area while I work Lackey and the goats are playing or at training class), but I’m not sure if that “counts” for the purposes of what you’re asking. I tend to feel it’s harder to teach them to stay on a target but have freedom to move on the target than “just” a sit, down, or what have you, but it doesn’t require much stillness. I’m not close to competition with her, so I tend to think of her stays in terms of how much can I accomplish during her stay. So I can nip into the house or garage to get something and leave her on a sit or down stay–so maybe a minute? I can certainly measure it.

So, I measured. I actually took two measures–one at the mall and one at home. I found that at the mall under heavy distraction, I had about 15 seconds if I could get a correct response to the cue, but correct responses were about 60% (estimate only, I forgot my tripod and my handheld video skills are apparently not that great). At home, I got about 35 seconds of down-stay while I set up. It took us a while to negotiate “you sit there and I don’t do anything,” but once we did that I think I had about 5 seconds of stay. (video)

I think that this is telling me that distractions actually serve as a keep going signal, and the shaping process has taught her that if I’m not providing feedback and I’m not doing something that doesn’t involve her, she’s to keep trying. So I think I haven’t trained the piece where she responds to the cue and confidently waits for some duration before receiving whatever the reinforcement is. It’s interesting that I now have two options on how to grow this–one to simply wait a bit longer before bridge + reinforcement, and the other is to pause a bit and then go off and do something unrelated (kgs). The first option has lower risk, but the second option has the advantage of building mass for stays during kgs. With either, I could try the 300 peck method. I’ve always found it appealing, because that reinforces each duration along the way. I know opinions vary on 300 peck–do you have any thoughts?

For readers not familiar with 300 peck, see https://www.equiosity.com/single-post/2019/02/21/Episode-49-The-300-Peck-Pigeon-Lesson

I have not found that new dogs are most likely to throw behaviors, and I’m speaking of training a few hundred new dogs. The ones most likely to throw behaviors are those dogs who have many behaviors that have weak stimulus control, and especially where the dog has not learned many, if any, long duration “holds,” I think most trainers call it. Call it patience, if you will. Particularly trainers with BCs, Aussies, Jack Russells, and other hi-energy dogs have problems with extinction because the dogs have not been taught patience. How? Simple long duration highly reinforced behaviors and held for many minutes, waiting for the dog to “calm down” and not be anxiously awaiting the release. Is it possible. Of course it is. But, if the life of the dog is constantly high-energy, and never is quiet part of the dog’s history, then the dog will be anxiously awaiting the next behavior. Combine that with poor stimulus control (weak cue control), and you have a dog that will throw, and throw, and throw behaviors during extinction. What will a new dog do. In my experience, if extinction is pushed too hard with a new dog it will simply disengage and look for a more reinforcing situation.

Yes, I wrote this article from the perspective that people trying it would have dogs with a large repertoire and not all under stimulus control. But I am more referring to dogs that have “patience”, but just have a hard time knowing the difference between their left and their right, so to speak.